Clustering the New Testament.

During Bible study last week, it was mentioned that people have used statistics to “determine” authorship of books of the Bible. Having a couple free hours last night, I tried my own experiment on the New Testament.

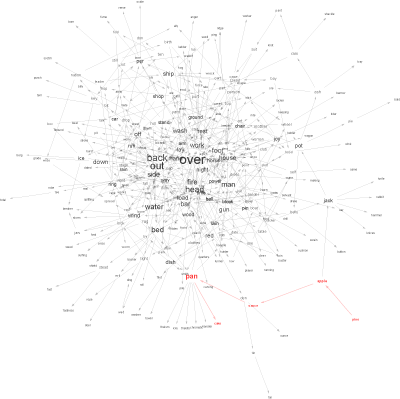

The procedure was easy: I downloaded the Nestle-Aland 26th edition of the New Testament; each book in the New Testament became a vector $v$, with $v_w$ counting the number of times word $w$ appears in the book. The cosine of the angle between two such vectors measured how similar the corresponding books are. I packaged these cosines into a matrix, the $(i,j)$ entry of which measured how similar books $i$ and $j$ are.

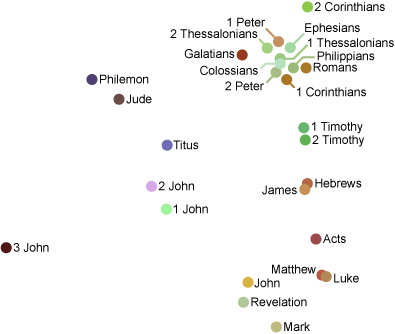

Of course, this is a $27 \times 27$ matrix. To turn these numbers into a nice picture, I projected the books onto a lower dimensional space spanned by the eigenvectors having the five largest eigenvalues (this is known as Principal Component Analysis); I chose five dimensions, displayed using location (two dimensions) and color (three dimensions, namely hue, saturation, and luminosity). The result is the following graph:

The dots represent each book, and nearby dots of similar colors represent similar books. Some things jump out right away:

- The Gospels are all in the lower right hand corner.

- Paul’s epistles (and Peter’s?) are mostly in the upper right hand corner.

- Revelation is close to John.

- Hebrews and James are close to each other? Why?

All told, I think this is a pretty good graphical display of the structure of the New Testament, especially considering we used nothing but the Greek text and linear algebra!

Posted: Tuesday, January 22, 2008 6:23:43am

Category: Theology

Permalink and Comments